Pack your rods and waders for an epic fly-fishing trip to Bristol Bay Lodge, arguably the most epic fishing experience on the planet.

BY ERIC LADD AND JOSEPH T. O’CONNOR

Tiny water droplets form and run up the windshield of the small floatplane as we cruise down to Rainbo camp. The fog is thick, reducing visibility to near zero and when the clouds part the vastness of this country becomes apparent. Creeks braid and meander through tundra fields as Troy Albplanalp, or “T-Bird” as he’s better known at Bristol Bay Lodge, expertly mans the floatplane, Ted Nugent’s “Gonzo” jamming on his iPod. We’re in the southwestern portion of America’s 49th state, surrounded by the Alaskan wilderness. Stunning, for lack of a better English word, is an understatement.

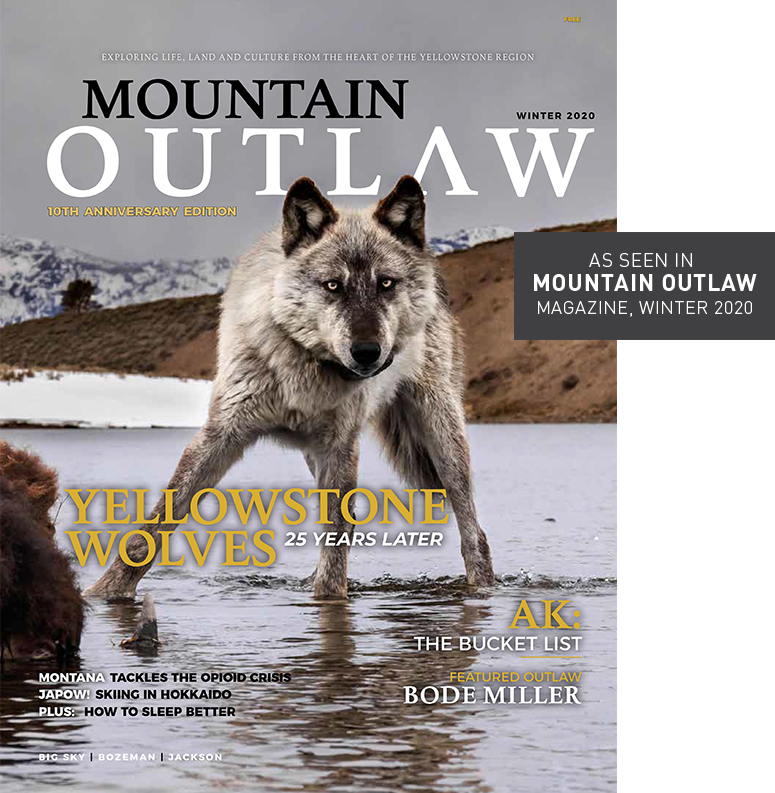

Visiting Alaska is a humbling experience that inspires, testing one’s will and connecting one with nature like no place on earth. In an era where growth and urban sprawl are headline news, the remoteness of Alaska has allowed the backcountry to remain intact and cities trapped in time. The one reliable outcome from a trip to

AK is a lack of prediction, much inspiration, the need for a good raincoat, a good chunk of time and extra memory cards for your camera. One must be prepared for a trip to Alaska, and especially for one to Bristol Bay Lodge. It’s the trip of a lifetime.

On a mid-September day, the fall colors paint the vast hillsides and valleys with every shade of red, orange and tan. Twelve friends and family have gathered for this pilgrimage into the AK backcountry with excitement brimming after four flights and a boat ride to reach this nirvana of fishing. Massive moose and bear traipse among a landscape absent of human impact; the sky is big, the weather aggressive, the people hearty.

Arriving at the five-star Bristol Bay Lodge, you’re welcomed to the “BBL family,” a business that launched in 1972 and is now run by seasoned guide, then manager and now owner, Steve Laurent. Laurent has a gentle but commanding presence having spent 29 summers in the Alaska backcountry sharing the rivers and mountains with guests and calling tents home for hundreds of nights. The lodge is complete with hot tub and sauna, and the highly trained staff takes care of every need, from stocking refrigerators in your room of the cabin to running daily loads of laundry.

For Laurent, who has now traded his tent life for lodge life as he runs his 20-plus guide operation and is also a talented pilot and photographer, his experience at Bristol Bay reflects a decades-long commitment to a place he truly loves.

“This was a calling,” says Laurent, 53, who first visited Alaska in 1990 as a college student at the University of Minnesota. “I talked to my dad and said, ‘Hey, I may have an opportunity to guide in Alaska. What are your thoughts?’ He said, ‘Listen, those are things that if you don’t seize that opportunity you might regret that in life.’ Now, 29 years later, we still laugh about it because I’m now an owner of a world-famous lodge in Alaska.”

Entering its 48th year, BBL is a well-oiled machine, taking guests deep into the Wood-Tikchik Wilderness to chase a variety of fish, and operating on six different rivers highlighted by two backcountry camps where guests stay overnight. Each day, clients rotate rivers and guides often accessed by floatplane and guests stay a few nights at backcountry camps, a signature moment for most trips to BBL. A trip to Bristol Bay is much more than a fishing trip, though. It’s a backcountry immersion experience where you happen to have a fly rod in hand.

“This is the greatest fishery on the planet for wild salmon,” says Laurent during one of the lodge’s five-star dinners, this one including massive helpings of Alaskan king crab legs. “You have to wear a lot of hats when you own and operate a lodge in Alaska. I love logistics but you can’t do it yourself, you have to have a great team.”

Running BBL consists of up to 29 staff members, three de Havilland Beaver floatplanes, and as many as 29 guests at a time over the course of a summer. “We’re busy,” says Laurent, a smile emerging from his brown and gray-flecked goatee. “I still lose 10 pounds a summer.”

One of the many unique aspects of the BBL fishery is the variety of options in these waters. Bristol Bay is home to the largest salmon run on the planet, including all five species: sockeye, coho, Chinook, chum and pink. But it doesn’t stop there. Starting in May and June, a massive king salmon run graces the waters in the Bristol Bay fishery, followed by the aggressive bite of the silver salmon, anchor-sized rainbow, dolly varden and grayling that pepper the catch throughout the season ending in mid-September. It’s not uncommon for rainbows to approach the 30-inch mark and king salmon north of 30 pounds to smash your line (though 50-pound salmon are not unheard of).

“Bristol Bay is one of the last places on earth of its kind and they’re not making any more like it,” Laurent says. “You can’t really describe it.”

At 663,268 square miles, Alaska is more than twice the size of Texas, the next largest state in the country. On March 30, 1867, the U.S. purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire for $7.2 million, or about 2 cents per acre.

- Alaska holds more than 3,000 rivers and 3 million lakes, the largest being Lake Iliamna covering 1,000 square miles.

- In 1985, auto dealer Les Anderson caught the largest king salmon ever recorded on a rod and reel. He landed the monster on the Kenai River. It weighed in at 97.5 lbs.

- Bear Necessities: There is approximately one bear for every 21 people in Alaska.

- Alaska has more coastline than the rest of the U.S. combined, about 34,000 miles.

The de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver is a single-engine, propeller-driven short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft developed and produced by de Havilland Canada. It’s primarily operated as a bush plane but has also been used in utility roles including cargo and passenger hauling, crop dusting and U.S. military search and rescue duties. Sir Edmund Hillary used the DHC-2 in his South Pole expedition from 1955-58 and the plane was named one of Canada’s top 10 engineering achievements of the 20th century. When manufacturing was discontinued in 1967, some 1,600 of these planes were in use.

The most remote camp in the BBL portfolio is an hour flight from the main lodge nestled riverside on what’s aptly named the Good News River. Dan Claus, a seasoned backcountry pilot with a dry humor, lack of hearing and incredible skills on the sticks, has been with BBL for more than 25 years. Claus flies a 1952 de Havilland Beaver floatplane and shows up to work layered in hoodie sweatshirts and hip-high fishing waders. The flight to Birch winds in and around the valleys and from the lofty view, passengers can glimpse the occasional moose or grizzly feeding in the wetlands and vast miles of stream banks.

Landing at Birch, the staff that lives there all summer greets you on the small pothole of a pond that doubles as the landing strip. Seasoned guide, Eric Mannon has been working at Birch Camp for 13 years and has a wiry frame, long hair spilling out from his ball cap and a Midwestern accent as he recalls tales from the summer. We land Mannon, 34, and his guide colleague Jared Koenigsfeld, 30, on their last trip of the season having been at the outpost for more than 100 days. Mannon’s wife works in Idaho and the only means of connecting is via satellite text, a recent technology upgrade for the backcountry guide. Few guides make it as long as Mannon and Koenigsfeld, who was closing out his sixth year on the Good News.

“This river we’re on … this place is magical,” Mannon says. “If you came every week of the year you’d see something different. It’s just full of epic days. It’s not a living, it’s a passion.”

Settling into our wall tent—a full and comfortable arrangement with soft beds and down comforters—we hear the guides announce the afternoon plan: “Hustle up, let’s fish for a few hours. The silvers are in!” Roger’s first cast in Alaska yielded a 9-pound silver salmon, a foreshadowing of the next 24 hours. The silvers have migrated 30 miles from Good News Bay in the Bering Sea to reach Birch Camp and are still fresh and aggressive. Late-season rains swell the rivers pushing the angling up the litany of back eddies and small side streams making the fishing even more dramatic: every third or fourth cast yields the equivalent of a cinder block on the end of our 8-weight rods.

Family-style meals are served streamside and on this night steak, wine and decadent chocolate cake help round out the hours of storytelling from the day’s adventures. Comments around the table include “… the biggest fish of my life” and “… the best day of fishing I’ve ever experienced.”

A short flight across the tundra revealed a horizon line with jetting rock islands and the Bering Sea. The smell of salt is in the air and pelicans and seagulls dot the open landscape. As the plane lands, we’re greeted by the staff and the guests departing after their 24-hour stay. The four brothers we’re exchanging spots with are on a heart-wrenching bucket list trip to Alaska and the parting comment from them was telling: “This camp was amazing, the fishing was unreal and Dawson’s cooking was the best!”

Rainbo Camp is situated on the banks of a large tidal zone and the tail end of the Nugukthik River where it enters the sea. It sees one of the largest tidal shifts in the world, and one morning hit 19 feet. The camp is staffed by three colorful personalities who recall tales of bears and star-filled nights, and endless hauls of monster fish.

At the tip of the Bering Sea, the camp is exposed to all the Alaska elements with bears trolling the shoreline, eagles feeding on chum and the occasional moose nestled in the bushes.

A picture-perfect afternoon greeted our group with calm air, deep falls colors and soft afternoon light on the tundra, a perfect reason to go fishing and some for a hike. The Rainbo fishery is a small river with twists and turns providing perfect runs, back eddies to target tailing salmon and endless side channels. Targeting any fish with a surface fly is considered by many seasoned anglers the holy grail of fishing and catching 15-pound silver salmon with a custom pink mouse patter called the “wog” was just that. The wog mimics a mouse having fallen in the water and swimming for a safe shoreline, and as you tease it across the surface, a v-wave appears behind it followed by an explosion of the fish take.

Back at camp, the group watches a young grizzly bear with a tan working the shoreline eating salmon while enjoying a glass of wine and watching the sunset.

Wood-Tikchik State Park sits north of Dillingham, Alaska. At more than 1.6 million acres and about the size of Delaware, Wood-Tikchik is the largest and most remote state park in the United States, comprising more than 50 percent of all state park land in Alaska and 15 percent of total state park land in the country. Wood-Tikchik was created in 1978 and employed no staff for its first five years, and even now sometimes a single ranger is tasked with patrolling the entire park, often by aircraft.

Life of Coho: Coho salmon, also known as silver salmon, can grow upwards of 30 pounds but most adult “silvers” run between 10 and 20 pounds. They mostly eat insects until they grow into small fish and shrimp hunters. Female silvers return from the sea to their original spawning ground in rivers to lay eggs, which hatch in late winter. The fry remain in streams for three years before returning to the sea as smolt. After about 18 months of feeding and growing into adults in the ocean, coho head back to their home stream to spawn. As the silvers swim upstream into freshwater, their sides turn red and their backs dark. They die within a few weeks of spawning and become food for bears and eagles, and as they decay their bodies release valuable nutrients into their home streams.

“The guides gave our group a quick one-hour fishing session that yielded 20-in-plus silver salmon, a large sow grizzly bear and a mother griz with three cubs, a lifetime cherished memory…”

Alaska is a guessing game: wake up and see what the day brings: weather changes quickly and extreme tidal fluctuations can dictate what the plan will be. Bad news hit our group on our Rainbo day when we learned we had to fly out of camp early because two converging typhoons off the coast of Alaska were bringing massive wind to this exposed piece of land. Before being whisked back to the BBL main lodge, the guides gave our group a quick one-hour fishing session that yielded 20-inch-plus silver salmon, a large sow grizzly bear and a mother griz with three cubs, a lifetime cherished memory all in the span of just one hour.

“Five minutes out,” BBL pilot T-bird radioed in and 28 minutes later we were back in the main lodge with a crackling fire in the two-sided fireplace and a three-course meal in the dining room.

Laurent is relaxed but drifts between guests cracking jokes and asking about their days. He’s put in another full week in another full season at his lodge but smiles, relaxed and satisfied. He draws a deep breath, exhales. “BBL is my livelihood,” he says. “I’ve got a lot of blood, sweat and tears here, but it’s more than that. I pride myself that I’m the same person in the spring that I am in the fall. If you love what you do, it’s easy. Just look at where you are. There’s nothing else like it in the world.”

As thick slices of apple cobbler are served for dessert, the conversation in the lodge is easy, ranging from the massive grizzlies fishing from shore, to the epic sunset that evening, to the camaraderie each guest has discovered in this wild and wonderful place. Bristol Bay, as we heard many times on this trip, is a bucket-list item to be crossed off.

BY JOSEPH T. O’CONNOR

On the fourth anniversary of National Salmon Day, October 8, 2019, five Alaskan native and fishery groups sued the Environmental Protection Agency for tabling Clean Water Act protections and fast-tracking a goliath mining venture in an area that also produces half of the world’s salmon: Bristol Bay.

If the proposal is granted, Pebble Mine would be the largest open mine in North America, unearthing some 1.5 billion tons of gold and copper, and residents fear the mine would threaten the area’s delicate ecosystem and its world-renowned fishing industry.

The 2019 season marked the second largest sockeye harvest in the fishery’s 133-year history as Bristol Bay commercial fishermen plucked approximately 43 million anadromous sockeye from their epic homecoming voyage to the freshwater rivers and lakes of their infancy— nearly doubling the 38-year average. It was a haul that emphatically justifies the 14,000 jobs supported by the fishery, a resource that has likewise sustained the region’s native tribes for centuries.

Last July 30, news that the mine proposal was again under consideration shook Bristol Bay Lodge owner Steve Laurent. Laurent is celebrating 30 years working at the lodge, located some 150 miles west of the proposed Pebble Mine site. He’s been in this battle for decades and worries an infrastructure failure at the mine would devastate Bristol Bay.

“This is the greatest fishery on the planet for wild salmon,” Laurent said at his lodge in early September. “I think it’s asinine that the Pebble Mine is even potentially back on the books.”

In an unsettled economy, nervous traders tend to shift assets into less volatile ventures. Some look to the healthcare sector or real estate plays. Others turn to gold and precious metals. “Copper Extends Its Rebound on Growth Optimism,” read a September 6, 2019, headline in The Wall Street Journal’s Business and Finance section. “Precious Metals Are On a Tear,” heralded another article in the same edition.

Shares of gold were up more than 30 percent since the beginning of summer, the article said, an indicator that a stumbling world economy, ongoing U.S trade wars with China and the threat of interest-rate hikes have investors worried. “There is so much flight to safety right now and metals is where that money is going,” Chicago- based commodities broker Bob Haberkorn told WSJ.

The debate over the mine is not a new one. For decades the Pebble Mine has been at the center of a heated controversy; on one hand, mining jobs and billions of dollars in precious metals are at stake; on the other, an entire ecosystem and a $1.5 billion commercial fishing industry in Bristol Bay, home to the largest sockeye salmon run in the world.

What is new is the timing: When the EPA loosened Obama-era mining regulations in Alaska last July 30, effectively throwing Pebble a renewed lifeline, the news rocked Wall Street. The next day, Canadian company Northern Dynasty Minerals, the sole owner of Pebble Limited Partnership, saw its stock skyrocket 65 percent, with shares surging from 54 cents to 91 cents, prompting accusations of insider trading. Northern Dynasty representatives have called the insider-trading allegations “entirely false.”

“This is the greatest fishery on the planet for wild salmon … I think it’s asinine that the Pebble Mine is event potentially back on the books.”

The proposed Pebble Mine location sits along the shores of 1,000-square-mile Iliamna Lake, the largest lake in Alaska, and about 125 miles from a fault line known as the Alaska-Aleutian megathrust, which saw the 1964 Good Friday earthquake near Anchorage.

The magnitude 9.2 quake was the most powerful ever recorded in North America and Laurent is concerned. Residents are also worried about toxic chemicals from mine tailings seeping into the water.

For its part, Pebble Mine operators claim that the mine infrastructure is sound, even in the face of a severe earthquake, and Pebble Group CEO Tom Collier has placed a zero-percent chance of irreparable harm to the Bristol Bay fishery. “Mine tailings are not ‘toxic,’” reads the Pebble Partnership’s website.

Covering more than five square miles and running nearly as deep as the Grand Canyon, the Pebble gold, copper and molybdenum mine in the Bristol Bay watershed would involve more than the mine pit itself.

“In total, these three mine components (mine pit, tailings impoundments and waste rock piles) would cover an area larger than Manhattan,” read the 2014 EPA determination referencing the Clean Water Act and curtailing the Pebble Mine proposal. Gina McCarthy, then head of the EPA under President Obama, stated that the mine would have “… significant and irreversible negative impacts on the Bristol Bay watershed and its abundant salmon fisheries.”

The 30-plus year tug-of-war has of late seen a renewed intensity. In May 2017, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt took the first steps to reverse the Obama-era EPA restrictions on mining in Alaska. On June 26, 2018—nine days before resigning his post under a litany of ethics scandals—Pruitt signed a memorandum limiting his own agency’s ability to curb projects on the grounds that they might pollute adjacent waterways.

His successor, Andrew Wheeler, has recused himself from Pebble Mine decisions because his former law firm provided services to Pebble developers. And in July 2019 the EPA, under pressure from President Trump and conservative groups including the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity, fully withdrew the 2014 determination and is currently reviewing the mine proposal with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

If granted the 20-year lease by the Army Corps of Engineers, Pebble Limited’s play would be worth hundreds of billions of dollars. The Corps plans to announce its decision to approve or deny the project in mid-2020.

Residents of the area wait and worry. “For me personally, the mine is something I don’t believe in,” said Rhonda Nicazio, a descendent of the Inupiat peoples of the NANA region who works at the air taxi service Fresh Water Adventures in Dillingham, Alaska. “Fishing is a way of life for most people in Bristol Bay,” she said. “It’s a natural resource that the community depends on.”

Eric Ladd is the publisher of Mountain Outlaw magazine.

Joseph T. O’Connor is the editor-in-chief of Mountain Outlaw magazine.