Four skiers talk the grit, the grind and the greatness it takes to rip with the pros.

BY BRIGID MANDER

The life of a professional freeride athlete is full of action, travel and excitement, but it’s no cakewalk getting there. We spoke with four athletes at different points in their careers about how they make it work, and what drives them in skiing and life.

Born in Big Sky, skiing has been woven into life for Riley from the beginning. She got her head start from her ski patrol father who was determined to share his passion with his daughter. He succeeded: Riley’s skills and strength as a freeskier caught the eye of ski photographers and sponsors, and now, as a college student, she’s embarking on the tough but fulfilling path of balancing passion for skiing and life, with figuring out how to make it all work.

On becoming a skier:

I was skiing before I can remember. There are definitely photos of me in a backpack as a baby when I went along on backcountry tours! Growing up, the Big Sky Ski Education Foundation had a ski racing and a freeride program. I did a couple freeride comps and I went back to racing, but my dream has always been to be in a Warren Miller movie.

On realizing opportunities in skiing:

My friend and I got to go heliskiing in Alaska for our 16th birthdays, and the guides thought I was a pretty good skier. So, I went and asked them what steps I could take to take my freeskiing further. And then I got a sponsorship from them [SEABA Heliskiing]. Last year, I reached out to other sponsors but then COVID happened, so that’s kind of on hold. It took me a while to approach new sponsors because I had thought if they weren’t reaching out, I wasn’t good enough. Finally, I learned that’s not how it works—you have to do all the outreach and work.

Now I’m a freshman at school [at the University of Utah]. This season I want to do some freeride comps, but just for fun, work with photographers I’ve met, and make some film clips. I’d like to do some Freeride World Tour Qualifiers, depending on COVID.

How will you navigate the future?

Even if my ski career does take off, I’m going to keep school at equal importance. I’ve always focused on school and skiing equally, so I’m going to continue my education toward studying law and skiing at the same time. It’s just going to take getting a lot of things done ahead of time.

Right now, I’m studying political science. My plan is to go into environmental law. Perspective-wise, skiing has completely molded how I think. I grew up outside, and I have a complete appreciation for the environment over other things. [Outside] is home for me.

McKenna Peterson is known as one of the kindest and most modest athletes in freeskiing for good reason, but she’s also one of the toughest and most talented skiers out there. We chatted with Peterson on her return home from the waters of southeast Alaska, where she captains the Atlantis, her 58-foot fishing vessel with her sister Dylan as first mate, from June to September each year. Following in their father’s footsteps, the point is to make plenty of money to ski—and not work—all winter.

On family traditions:

My parents were big skiers. I grew up in Sun Valley skiing, ski raced till freshman year in college, and then paid for school [at the University of Utah] with fishing and bartending. My major was physiology with a minor in nutrition to go into some sort of medical field, but I always knew my life was going to include skiing as a central part.

On fortune and expectations:

I figured I’d be done with [professional] skiing by 30, but it’s the best it’s ever been. I’m making money and I’m having fun, so why not keep rolling with it? But I know I’m not going to do this forever, and there are other things I’d like to experience. Learning to run the [fishing] business, and meeting people who aren’t part of our small resort towns has been great.

On risk and balance in life: (note: McKenna’s father Chris Peterson perished in a 2016 avalanche accident; her two siblings also remain involved in the ski industry and are big mountain skiers.)

It’s a part of skier life, our family accepted the risks. My dad had skied the backcountry for so long and was so experienced and well educated. But seeing that happen has made me more conservative. I furthered my backcountry education and I still have full support of my family. We all still ski.

On standout moments of a full career:

A trip I always remember was SheJumps’ Alpine Finishing School in 2011, which really stoked my passion for ski mountaineering. The most fun film I’ve been in was Lynsey Dyer’s Pretty Faces (2014), where I got to be in a movie with all my idols, and it inspired me to try harder to do more filming. Last year I got to film with Matchstick Productions for Huck Yeah! and that was always a big goal of mine.

What’s next?

This winter I’ll film with Matchstick again, and we’ll keep it local for the most part. I hope to explore zones close to home this winter. After all, I live in Sun Valley for a reason.

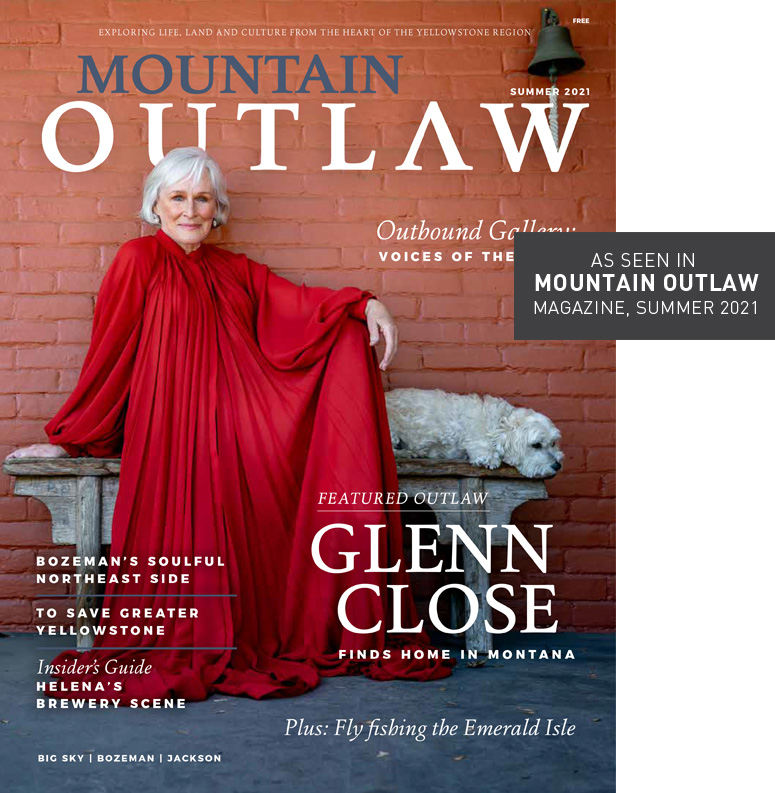

Passion for skiing isn’t always a direct genetic and lifestyle line. Caite Zeliff was the daughter of a single, non-skiing mother. She did, however, have the fortune to grow up in North Conway, New Hampshire, and go to an elementary school with an affordable lunchtime skiing program. Zeliff found her calling, and sheer determination and athletic talent have brought her opportunities—albeit not the ones she was expecting—to fruition.

On entering the ski world:

My elementary school program was my first taste of skiing and the sense of freedom it can provide. A friend eventually told my mom about a ski racing program—I won my first race and got so much confidence from that trophy! I became obsessed with skiing. My goal was to be on the U.S. Ski Team.

On the interference of fate:

I then went to UNH [the University of New Hampshire] to ski race Division I, then I blew my knee out. I suddenly just felt relief: I could stop killing myself for racing now. I quit school and moved to Jackson, Wyoming, at 20 just to ski. Ski racing was too much, but I realized with freeskiing I can still work hard as an athlete and have some fun and be creative.

Someone told me I should do the Kings and Queens of Corbet’s [competition]. I’d never skied Corbet’s and didn’t want to do it, but I reached out. My first run was like a flying squirrel in the air; I thought I was gonna die. The next run was smoother, but I didn’t expect to win.

After I won … suddenly I had all these Instagram followers and Warren Miller Entertainment reached out to me. The next year I won that competition again, and I got a call to film with Teton Gravity Research (TGR), and last year I got a full segment in Make Believe.

On making ends meet while skiing all the time:

I had gardening jobs in the summers, and slinging food at night at Teton Thai. In the winters, I did the restaurant at night, and ski instructing and coaching during the day. The gardening was the most impactful though—I didn’t have time to be in the gym training while working so many jobs, so manual labor was helpful! I’ve been able to phase out of working so many jobs, and I’m taking skiing really seriously. I try to be transparent about the struggles of “living the dream.” Sometimes ski stars are still slinging drinks!

Winter plans?

This season is going to be weird. But I’m filming again for a segment with TGR! I have a lot under the hood still, and I’m also still figuring out myself as a person and a skier. I make sense of a crazy world by connecting over the outdoors—life makes the most sense there.

As a kid in Montana, Erika Vikander grew up chasing her older brother around Bridger Bowl on snowboards and making the occasional trip to Big Sky. She didn’t know at the time she could make a career out of snowboarding, but once she figured that out it was full steam ahead for this now successful, globe-trotting, full-time athlete.

On taking chances on an unusual dream:

I had a full ride scholarship to play soccer in college but I decided to pursue slopestyle snowboarding. So, I skipped college.

In the last three or four years, I made enough from sponsors to support myself. Before that, I worked in restaurants, coffee shops, construction, retail—you name it, I did it—and also made sacrifices like not going home for Christmas because I needed all the money for snowboarding.

On twists of fate:

One of the worst side jobs was part of a blessing in disguise. I was all set to go to the Sochi Olympics for the U.S. in slopestyle when I blew my knee out. I had no money; I’d spent it all on training. I had to get a job driving an airport shuttle from Breckenridge to Denver, and there I was, loading tourists’ ski bags instead of going to the Olympics. I hated every minute of it. I took a full year off to recover and then someone suggested I try a big mountain competition.

[After a few qualifying competitions] I made it onto the Freeride World Tour (FWT) and I was just like, “Yay, I made it! Just don’t die…!” I mean, I came straight out of the terrain park. At my first big mountain competition, the Subaru Freeride Series in Snowbird, Utah, I even asked another competitor what “fall line” meant … I still feel dumb about that one.

On achieving the dream:

I’ve had to be really self-motivated to make it happen on my own. Sometimes I’m gone half the year. Living out of a suitcase sounds romantic and all but it can be really hard too. I’ve also gotten a lot better at balancing my life. I live now in Hood River and Mt. Hood. It’s not the most aggressive terrain, but I have a great quality of life!

What’s next?

This year, the FWT is on so far, so I’ll compete and travel, but I’m also making a film with Picture Organic, kind of an eco-friendly passion project I’m excited for. I’d like to keep competing on the FWT for a few more years, and snowboard professionally as long as I can. After that, I don’t need to be a millionaire, I just want to be outdoors doing fulfilling things with good people.

Brigid Mander, is a skier and writer based in Jackson, Wyoming, who prefers uncomfortable travel to hard-to-access—therefore, uncrowded—places. Her work appears regularly in publications like Backcountry Magazine and The Wall Street Journal.