Montana’s winter sets a new stage for its wildlife.

BY JEN CLANCEY

One of the wonders of Montana is the wildlife it hosts, its magnificence due in part to the resiliency needed to survive in an often-harsh environment. Montana’s winters illustrate this best, challenging its living inhabitants with blustering winds, freezing temps, dumps of snow and all the side effects of such conditions—especially in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

As a Yellowstone guide for more than 30 years, Denise Wade knows this best. Since 2018, Wade has co-owned Big Sky Adventures & Tours, and her clients are treated to a unique experience in the snowy season.

“A lot of the winter tours definitely focus on talking about adaptations that wildlife has to make to survive the winters here,” Wade said.

Whether you’re on a tour with Wade, out on an independent adventure or are simply observing the outdoors from your living room window, enjoy Mountain Outlaw’s field guide as a way to study and appreciate some of Greater Yellowstone’s hardy wildlife—and keep your eyes peeled!

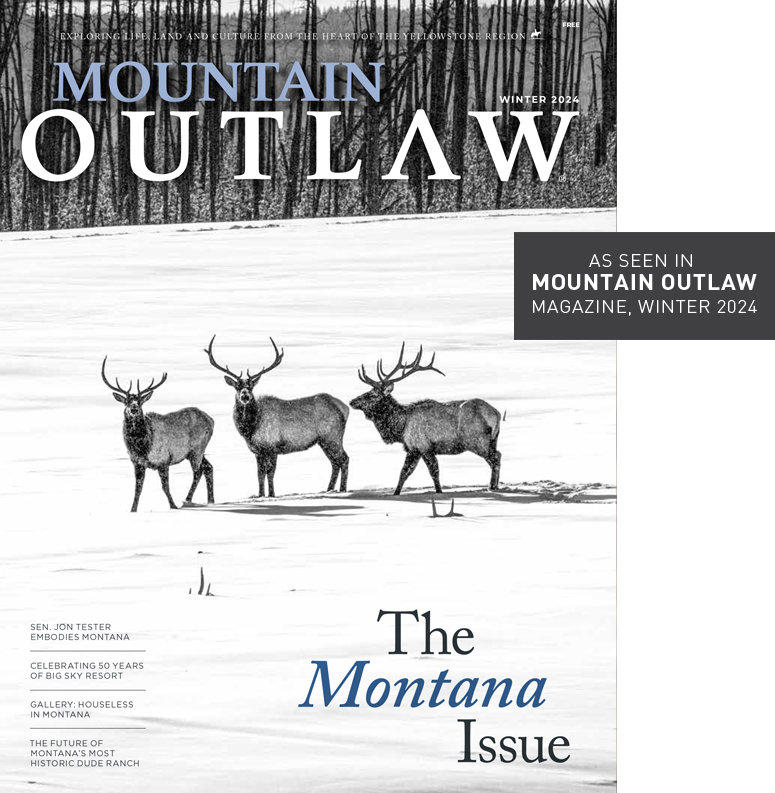

Elk | Cervus canadensis

According to the National Park Service, elk are the most abundant large mammal in Yellowstone. In the winter, their population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem decreases from summertime’s 10,000-20,000 to less than 4,000. Even with smaller seasonal herds, they are an essential food source for winter predators, composing 85 percent of wolf kills and supplying eats to 12 scavenger species.

A bull elk’s age can be identified by the size, width and number of points on their antlers. At 11 or 12 years old, an elk will likely have the thickest, heaviest and largest antlers in its lifetime. After that, their antler size will decrease. As spring rolls around, you may have a better chance of witnessing evidence of an elk’s path: shed antlers are replaced by new ones in the warmer months.

FUN FACT: An elk’s color changes from light tan in the spring, fall, and winter, to copper brown in the summer.

Courtesy Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

Long-tailed Weasel | Neogale frenata

While the long-tailed weasel is the largest and most widely distributed of the three North American weasels, you might have a hard time spotting them in the winter. During the spring and summer, the weasels sport a brown coat with a white stomach. But when snow begins to fall, their coats become entirely white as they transform into their winter version, the ermine. Not only does this allow them to hide from predators, but it also camouflages them when they are on the hunt for voles, mice, pocket gophers, smaller birds and rabbits. During the spring and summer, they add various reptiles and amphibians to their diet.

If you are keen to find these elusive winter creatures, here’s a tip from Wade: “Trying to follow their tracks isn’t something that’s going from point A to point B. It’s this really crazy… track pattern, but it’s because they’re listening to the mice below the snow, and are following exactly on top of wherever that mouse is moving.”

The 13- to 18-inch long mammals will likely be seen alone as they are solitary animals.

FUN FACT: The long-tailed weasel’s presence spans from southern Canada to northern South America.

Courtesy University of Minnesota-Duluth

Peregrine Falcon | Falco peregrinus

Because these birds are mostly seen from March through October in the Greater Yellowstone region, it’s a real treat to spot a peregrine falcon during the winter. Coasting at 55 mph when flying, these falcons travel at speeds up to 200 mph when attacking prey—mainly songbirds and waterfowl—in mid-air.

“Peregrine falcons are beautiful to see,” Wade said. But for the more casual bird spotter, she advises looking out for eagles if you’re itching to see a predatory bird. “We do get a lot of bald eagles that come down from Canada during winter here. So it’s really common to see bald eagles in the winter, more so than the summer,” Wade said.

The falcons’ population began declining in the 1940s due to impacts from pesticide use. During the 1980s the National Park Service launched efforts to reintroduce the species through captive-bred peregrines, releasing them into Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. In 2022, the park service saw at least 21 young in studied territories.

FUN FACT: The falcon’s name, derived from the Latin word peregrinus, means “to wander.”

Courtesy American Bird Conservancy

Mountain Lion | Puma concolor

The cougar, also known as the mountain lion, can be confused with the jaguar of New Mexico and Arizona, but is a smaller species that dwells in more rocky and rugged territories of the West. Due to their elusive nature, cougars narrowly survived an early 1900s campaign to kill off predators. According to the National Park Service, cougars were all but eliminated from Yellowstone National Park but began a slow return to their historic homelands in the 1980s.

Wade says cougars are among the rarest animal to see during both her tours and own personal animal-watching. “Cougars are really hard to see. And for me personally, that’s where looking for wildlife tracks and putting together those clues of tracks or scat or rubbings on trees or scratch marks [is important],” she said.

There are an estimated 32 to 42 cougars in the northern portion of Yellowstone National Park, and they are most often seen through the lens of remote cameras and webcams. In the summer, cougars tend to remain at higher elevation but as the weather turns colder, they begin to descend.

FUN FACT: On average, cougars kill elk every 9.4 days and spend about four days with each kill.

Courtesy National Park Service

Jen Clancey is the digital producer at Outlaw Partners.