With a population of 800, Philipsburg, Montana, consists of a few colorful blocks lined with gem stores, hotels, historical museums, restaurants, and a brewery with a statewide reputation.

BY SARAH GIANELLI

This story began with a dart toss. I was blindfolded and spun around before taking aim at a map of Montana. Wherever the tiny arrow landed, I would go in search of the soul of that place.

My first attempt missed the target entirely and landed in a flower pot. My second toss landed in a sparsely settled region of western Montana near Georgetown Lake, a predominately summertime community where the main attraction is a 2,800-acre reservoir known for some of the best fishing in the state. In high season, the population swells into the thousands and dwindles to a few hundred in the winter. In mid-March, winter was still going strong.

Georgetown Lake has two year-round businesses, both bars, and they seemed like a good starting point. After a long loop around the lake, past vacant, snowbound summer homes, I pulled in to Seven Gables Resort, a watering hole just off Montana Highway 1 at the turnoff to Discovery Ski Area.

With no other patrons in sight, the bartender, Summer Payne, had plenty of time to chat. “So long as you don’t ask me about my ex-husband, the Montana militiaman,” she said with a laugh. She was referring to Ryan Payne, who was involved in the anti-government wildlife refuge takeover in Oregon, and had recently been sentenced to 37 months in federal prison.

Originally from California, Summer Payne has lived in the area for 10 years and said she’d never leave.

“I love Montana. I love the people—everybody’s friendly around here. People wave when you go through town; if you break down or get caught in a snowbank, someone is going to stop and help you,” she said.

When Payne’s house was broken into and she lost everything, the community organized a fundraiser that helped her refurnish her home and care for her kids.

When asked to share some stories about the locals, Payne said, “Nope, nothing that I can share … we’re pretty tight-lipped around here about what we do.”

She suggested I head to Philipsburg, a former mining-turned-tourist town about 10 miles to the north.

“Whether we like to admit it or not, we are now a tourist town.”

With a population of 800, and located halfway between Yellowstone and Glacier national parks, Philipsburg consists of a few colorful blocks lined with gem stores, hotels, historical museums, restaurants, and a brewery with a statewide reputation.

I popped into the town’s famed candy store, the Sweet Palace, where I met proprietor Shirley Beck, a short, spunky redhead in her early 70s. Her spiel about the shop and her neighboring sapphire gallery was as polished as the emporium’s pink embossed-steel ceiling.

Beck has owned the Sweet Palace for more than 20 years, and is nearing her 40th year as an area resident—she’s also a fierce champion of the town’s tourism-based economy.

In 1988, after renovating the community’s 100-year-old grocery store, she and her business partner, Dale Siegford, combined their sales and gem expertise, and opened a jewelry gallery that features the sapphires found in the surrounding mines.

A few years later, Beck felt the need to diversify and she and Siegford opened what is now one of Philipsburg’s main attractions. “Philipsburg was dying and in pretty sad shape when we [opened the Sweet Palace] in 1992,” she said. “There were tumbleweeds in the street.”

Beck’s been an officer of the Philipsburg Chamber of Commerce since 1990, and pointed to the town’s resourcefulness throughout its boom and bust history.

“I happen to think there is no such thing as luck; I think you make your own luck,” Beck said, adding how crucial it is to be able to spot opportunity. “[Then], can you turn around on a dime to make it work for you?”

I passed a group of happy beer-drinkers soaking in the sunshine outside of Philipsburg Brewing Company and wandered down Main Street. The ornate, Crayola-colored Victorian facades quickly faded into unassuming homes with leaning picket fences and wrought iron doors.

At the corner of a muddy, potholed lane, a sign read Woodland Creations and Home Store. I walked through puddles of melting snow and a jumble of trailers, cabins and rusty relics to a large warehouse. Behind the counter, surrounded by a catchall of coffee and pastries, locally made arts and crafts, lumber and general hardware supplies, was Charity Therriault-Lemke, a 36-year-old born and raised in Philipsburg, who soon proved worthy of her namesake.

“He’s the biggest character you’ll ever meet,” she said about an old miner who went by the name “Wild Meat.” “When he was younger, he lived on wild meat, like, literally that’s all he ate—at least that’s what they say.”

She drew a map to Wild Meat’s home, located in an abandoned mining camp in the hills above town. When asked if she was sure it was OK to just drop in on him, she shrugged and simulated pumping a shotgun.

“I’m proud of the heritage, the town, the resiliency of the people—people who have stayed here in Philipsburg when it would’ve been a lot easier to go somewhere else.”

Deciding it wasn’t respectful—and possibly dangerous—to show up unannounced at Wild Meat’s front door, I stopped at the brewery where I met a host of longtime locals who would get me closer to the old miner, and share stories of their own.

Inquiring about Wild Meat, I was directed to Sam Dennis, a 32-year-old with family roots in Philipsburg dating back to 1877, when his great-great-great-grandfather arrived to work in the mines.

“I could never leave because this is my home,” Dennis said. “I’m proud of the heritage, the town, the resiliency of the people—people who have stayed here in Philipsburg when it would’ve been a lot easier to go somewhere else.”

His ancestors worked in many industries over the years. His grandfather was “a sawmill man,” a logger, a milkman; his uncles were miners. He said that one side of his family, the Winninghoffs, owned the first Ford dealership in Montana, and his great-grandfather opened the original Sweet Palace in 1934.

“In ‘92, Shirley Beck approached my grandmother about using the name, and the Sweet Palace came back to life,” Dennis said.

When he was a kid, Dennis said that the lively brewery we were standing in, once a bank, was boarded up with broken windows, as were many other storefronts in town.

The logging industry had all but disappeared, as had mining; and he said that ranching—his parents’ livelihood—has been the sole provider of any economic stability for the region over the long term.

“It’s changed a lot,” Dennis said, reflecting on Philipsburg’s shift to a tourism economy, a touch of regret in his voice. “[But] it’s brought a lot of life back … when, honestly, it was dead and dying.”

He said mining has attempted to make a comeback a few times, but he thinks it’s over for good. “Whether we like to admit it or not, we are now a tourist town.”

Wild Meat isn’t ready to accept that fate, though. Dennis arranged for me to meet the old miner the next morning at a house in town where Wild Meat had rebuilt a two-story piece of mining equipment resurrected from a defunct gold mine he owned northeast of Philipsburg.

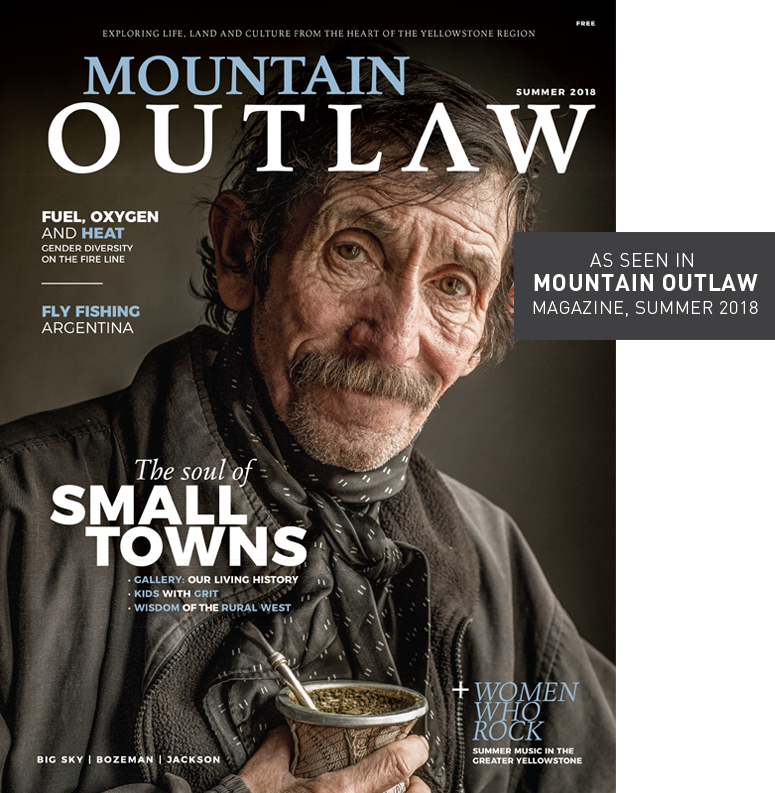

Wild Meat, whose real name is Dave Harris, was not the threatening hillbilly the townspeople had let me to imagine. Gruff, yes, but it seemed to indicate a disposition accustomed to solitude more than a dislike of prying outsiders. Warming him up with some small talk, I inquired about his unusual nickname.

“I got that when I was 21 years old,” he said. “I mostly lived on elk meat and somebody just hung that name on me.” When he mentioned his 74th birthday was the following month, I asked if he’d lived in Philipsburg his entire life.

“Well, not yet,” he said sarcastically. Crunching across the snow to the stamp mill he rescued from ruin, a taciturn man turned into a verbal encyclopedia.

Built in 1892, the Stamp Mill consisted of 900-pound steel grinders that moved up and down to smash raw ore into a pulp from which gold particles and other precious metals could be extracted.

He became animated when talking about the machine, shaking his head in awe of its massive parts, the crane it took to move it piece by piece, putting it back together, and the first time he got it to run again. Last summer, he and the six other men it took to operate it, fired up the stamp mill for a demonstration during Philipsburg’s annual Miner’s Union Day celebration.

“There used to be hundreds of these mills around the Western mining camps,”he said. “This mill here is one of only 16 operating stamp mills in the country now.”

Wild Meat had mined in the area—and anywhere else he could find work—for 30 years, searching for silver, lead, zinc, tungsten, manganese, gold—whatever was in the ground and in demand.

“It seems like the younger people don’t have any interest in this. One hundred percent, it’s a tourist town now,” he said. “It was always a working town when I grew up but it’s quite different now.”

Wild Meat spent a good portion of his life underground, at depths up to 1,800 feet, but isn’t able to describe the experience. “I couldn’t make you understand. It’s a different world.”

After the tour of the stamp mill, I followed his old flatbed truck up a dirt road toward his homestead in the hills, past mining wreckage that looked like enormous piers that had slid from the hillside and splintered into disarray.

Most of the mines were still operating when Wild Meat moved up there in the spring of 1966.

His property is scattered with old mining cabins, most built between 1875 and 1890. He lives in the newest building on the homestead—a green log cabin built in the mid-1950s.

An antique, wood-fired stovetop occupies one corner of his kitchen, antlers hang on the walls, and mining photographs and memorabilia are everywhere. He rifled through yellowed papers and fuzzy black and white images, describing the history behind each one.

A bronze bell from a mine he worked in “a couple of gulches over,” hangs on the wall, its hammer still capable of sending ringing vibrations through the room. The bell was used to signal to the men in the shafts when it was time to hoist materials up to the surface.

Wild Meat speaks wistfully of the past, and though eager to see a revival of mining, he isn’t very hopeful.

“The shafts, the timber, they never kept it up,” he said. “Now it would take many millions to get it going again. Then you’ve got people moved in here that are pretty hostile to mining.” I asked him how he felt about environmentalists, and he said his answer wouldn’t be fit for print.

After an emotional parting with Wild Meat—who seemed reluctant for me to leave—I made one last stop to fill in a missing piece.

Charity Therriault-Lemke had offered to take me out to an area ranch, so I followed her to the Rock Creek Land and Cattle Ranch, a long 9 miles outside of town, where she introduced me to ranch manager Kurt Loma.

A man with an impressive build and good-natured demeanor, Loma said ranching has always been the mainstay of Granite County. He spoke of challenges that require a strong will and stronger back, the tightly woven community, and its allure for him personally.

“It’s the lifestyle,” he said. “Where you get to live, not having to answer to anybody. It gets in your blood and it’s hard to shake it.” A working rancher, an aging miner, a young man whose blood runs 150 years deep in Philipsburg— and even recent transplants—all share an unshakeable conviction that they’ll never leave.

“It’s that pioneer … that real Montana spirit that keeps people here generation after generation,” Sam Dennis said during our conversation at the brewery. “It makes you tough. And it makes you stay here no matter what.”

Sarah Gianelli is the former senior editor of Mountain Outlaw magazine.