BY BRIAN LADD

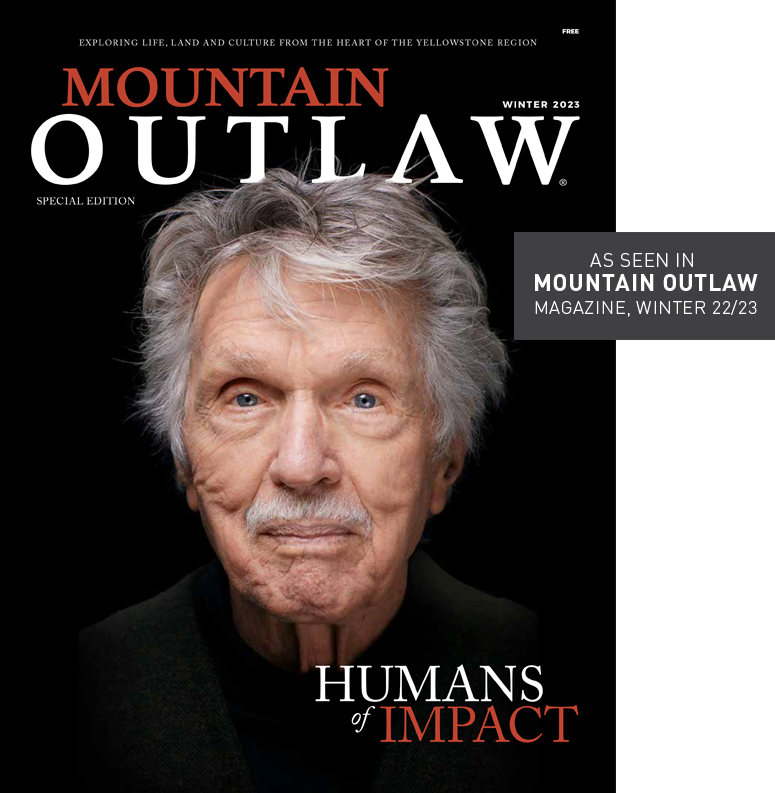

The crisp Pacific Northwest air was illuminated by the morning-angled sun; gold, amber and purple hues reflected in the oak and maple leaves outside. I’m sitting with Tom Skerritt at the stately Seattle Tennis Club overlooking Lake Washington. We’re a long way from Montana, but when the renowned 89-year-old actor starts waxing poetic about rivers, I feel like I’m sitting with him on the banks of the Gallatin River, our feet dangling in its cool, free-flowing waters as he describes the rhythm of the current.

Reality blurred as I looked at who I knew as Reverend Maclean, the Scottish-American Presbyterian minister and father in Norman Maclean’s renowned novella A River Runs Through It, played by Skerritt in the film adaptation of the book. Perhaps to some Skerritt may appear as Top Gun’sCommander Mike “Viper” Metcalf, or to a more obscure bunch he might be known as Duke Forrest from 1970’s M.A.S.H. But I suppose in reality, he’s just Tom; a father, grandfather and conservationist with a lifelong deep love for rivers.

The distorted reality warped further as what I intended to be a linear conversation about river conservation shattered into a two-hour artistic smattering of Skerritt’s deepest musings. Skerritt wove a melodic interplay between the past and the future, reality and aspiration, with a trajectory converting mundane to import. It was only later with reflection on our interaction that my understanding of his words grew.

“[In] life the best of what we have is that which we feel.” – Tom Skerritt

Though the way he discussed rivers with me remained mostly abstract and whimsical, his impact on them has been anything but. Skerritt served for nine years on the board of directors for American Rivers, one of the most well-known river conservation organizations in the nation. His tenure notably included the historic removal of the Elwha and Gline dams on Washington’s Elwha River in 2011, a monumental win for proponents of free-flowing rivers—Skerritt attended the removal and emceed the ceremony.

On the American Rivers board, Skerritt says he was always surrounded by incredible scientists and experts and always made a point to listen rather than to interject, but he brings something altogether different and perhaps equally impactful to this conversation: passion. You see, when Skerritt talks about rivers, he uses the language of emotion.

More recently, Skerritt’s been especially active in advocating for rivers in southwest Montana, where so long ago he first dipped his toes into waters of the Gallatin as Reverand Maclean.

“Filming A River Runs Through It was a transformative experience,” he posted on Twitter this year for the film’s 30th anniversary. “The beauty of the Gallatin River has remained with me all these years. But now, due to industrialization, it’s under threat.” He compelled his audience to follow the Gallatin River Task Force, a Big Sky-based conservation nonprofit working in the Gallatin River watershed, and a region with which Skerritt is becoming increasingly involved.

Late in his life now, Skerritt sees rivers as a force that can illuminate our interconnectedness. Decades after playing the role of Reverand Maclean, he says now more than ever he understands Maclean’s famous words: “Eventually, all things merge into one and a river runs through it.”

“But how do we take care of the river that serves all of us? Without this river we don’t exist.” – Tom Skerritt

Mountain Outlaw met with Skerritt in November of 2022 to discuss his relationship with rivers, their significance and our role in protecting them.

Mountain Outlaw: When and where did your love and passion for rivers begin?

Tom Skerritt: Why don’t I just flashback to when I was a kid and my father or my brother … taking me to go fishing, and I remember most putting my feet in cold water rushing by and the feeling of that. They’re out there busy fishing and getting caught in the trees and all of that bad casting—of which there was quite a great deal of it—and I’d watch them and the rhythm of it.

Also at the same time at home, I had an older brother who would babysit me when my folks weren’t around and he would put music on to keep himself from being bored and it was music that could be jazz [like] Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, somebody like that … or Puccini’s opera! He was 16 years old, I don’t know where he got that good taste, and I didn’t know what I was listening to. But the rhythms of that were suddenly what I felt. Looking back on it and understanding the rhythms of life, what I was feeling rushing by [on the river] was that same feeling of coming to know that which you had no idea what it was. I mean, putting your feet in cold water rushing by and listening to Billie Holiday singing the tune … there’s something about it that you are moved by internally, and it’s not something that’s explicable. It’s something you just feel. [In] life the best of what we have is that which we feel.

MO: That’s a beautiful account of your early history with rivers. How do rivers continue to contribute to your story today?

TS: I have five kids … They’ve all come back here and I think they’re watching me grow old. They’re just wonderful people. And [I have] five granddaughters—all gorgeous and whatnot. And I just had my first great-granddaughter. So all of that, it’s quite moving, because you’re gonna look back and we’re talking about the same thing: history, our histories, what we are, who we are and everything—where we grow up. And this country, this land, it’s the best piece of real estate. This is United States. There’s nothing like it anywhere. Having traveled a lot and been in other countries, [there’s] nothing like this. So that’s where we start is just first of all appreciating where we are … I have five kids, five granddaughters, a great-granddaughter recently and the honor of that, experiencing that, and the importance of it is undeniable. But I wish I could take them to the rivers.

“At sunrise everything is luminous but not clear.” – Norman MacLean

MO: What do we have to learn from rivers? What do they mean to us?

I remember too, as a kid, watching the rivers flowing, and you know, you dangle your hands in them and you think, ‘Wow, where does it start and where does it go?’ And as I grew up, it stayed with me as a kid. I think [about] all that music that my brother gave me [and] the rhythms of it and the feeling. The feeling of it was here in the water. In jazz you didn’t know what was coming up next. And you really don’t know about the rivers, the way they ripple, the way they kind of wash along the edge, and you know, there’s one big [trout] over there by that rock, just behind that rock. And [there’s] all of these questions you have, but it’s just water flowing. Where does it start? I used to wonder ‘where does it start? Where does this end?’ It’s like a train, or listening to the longer distance of a train—the sound of it: (Skerritt hums, his vibrating pitch rising and falling). You know, the horn, the sounds of it, one way or another, the whistles, all that kind of stuff as a kid.

I think da Vinci once wrote ‘you put your hand into water and feel the rush go by through your fingers, and you feel the past, the present and the future.’ And that one I remember as a kid reading that and I thought ‘what does that mean?’ But it stuck with me somehow, there in the imagination. It’s one of those remote things. Leonardo da Vinci, he’s a painter, right? There’s nothing he couldn’t do, I mean he was a timeless genius. But it’s so true. It’s so easily that you understand that: you put your hand in the water and [it’s] the past, present and future rushing through your fingers. You can’t explain that. You have to know what it feels like to do that … You know, you dangle your hand out there, maybe you’re gonna wash off some of the oil from a fish, or whatever it is.

All of that stuff was what I got as a kid and I never knew quite how to utilize it but I was informed because I had a very active imagination apparently when I was quite young and I know that was activated by being in school … they had these creative programs in grade school which I guess they don’t have anymore and I think it’s part of a crisis we’re facing is we seem to lack a really truly informed imagination. So that’s what I feel I had was an informed imagination … It goes on and on, the wonder of it … the rivers always seemed to me that kind of thing that goes on and on and on. Where’s it coming from? Where’s it going to? And what’s this life in here and how do these fish know that there’s a certain bug that comes out at a certain time of year and they know what part of the river it goes to? Is that not something to respect? Is that not a degree of intelligence of that life compared to ours? In a lot of ways, I don’t know really the difference when you sit there with your legs in the water wondering that sort of thing.

I’m not trying to be romantic about it but the practicality of what we’re trying to do by making more money or helping companies do better. Let’s modify our lives. And it’s not condemning anything, it just said, look in the mirror. Are you a little bit older? What do you look like? Laugh at yourself … and say ‘You crazy old man.’ And that’s what I say to myself. A male ego has taken over. A male ego is just one who wants to rule over others. American males have started wars for centuries. What are we suggesting here? There’s something at once very feminine, very male about the river. … The edge of it is beautiful. That’s the female; the water soaks in there [and] grows the cottonwood trees. All of this is the connection. We’re not alone.

“As long as we have a healthy river, we have hope. If we don’t have a healthy river we don’t have hope.” – Tom Skerritt

MO: What are the issues we face as a society in terms of the ways we engage with rivers, and the ways in which we seek to protect them?

TS: It really has to do with what’s happened to the waters. That’s the heart of what we’re talking about … I was on the American Rivers board for nine years. I listened rather than try to [interject] anything in conversation, particularly with the professionals and science and some very, very significant people on that board. They were worth listening to. … I really have always appreciated the information and vast intelligence of this group of people. But I’m missing [where the] heart [is in all of this]. We talk about what we can do here and there, but what? What can we do about enjoying? How do we really enjoy this?… I was trying to say that if you want people to donate—which is a lot of what they were talking about—to American Rivers, I just feel we’ve got to get more [at] the heart of it …

But how do we learn to be better if we don’t make mistakes? … How can we turn this around? What’s happening with the rivers? We’ve known this for a long time, which is one reason American Rivers started in the early ‘70s was to make sure that the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was enforced and acted upon by the government as was expected because that stuff tends to wander away. All good intentions are spoken over the microphone, and then they go off and play golf or whatever it is. They don’t get it done. And the American Rivers was there to say ‘please, I’m here. I’m paying attention. I’d like to help you. Let’s work together.’ … We have to be stronger about this, we really have to …

I feel I’ve got to find the right words, as we all must, to be able to say what we really feel about things, and the rivers really are us—they’re the blood of the system, the vessels that go from the heart, which is the snow melting … But how do we take care of the river that serves all of us? Without this river we don’t exist. That’s a big one. And I don’t take that lightly and that’s why I’m very emotional about this.

MO: An objectively huge moment in your tenure with American Rivers was when you attended and spoke at the largest dam removal in history on the Elwha River in Washington. How do you reflect on that significant moment in your journey as a conservationist?

TS: That’s an interesting throwback. I remember that. First of all, prior to the dam going down, a group of us for the American Rivers went up to look at and visit two dams … I had walked out on that dam, and I looked down at the pools that were there. And in each one of them were some salmon swimming. I said that can be only generations from over 100 years ago, still spawning somehow, and knowing that they want to go upstream just circling, waiting for the water to come down so they can fight it up there. And you start processing … I didn’t know how to find the right words to say what I felt. And I remember looking at that [and] thinking ‘wow, those guys [have been] hanging around waiting for [the dam] to come down, 100 years of this of one generation after another waiting for it and they knew what was going to happen. I make believe, obviously, but that never left me. And then [they] tore that down.

This is a river that had all five salmon [that] used to swim all the way up the top. And they were the biggest salmon ever. Because it was the struggle of getting up that river, the struggle of going out solo [to] the ocean; [it was] always a struggle. And I’ve lived my life that way. So I could relate to it. It’s all a struggle; the more you struggle, the more you get up that stream. And you get up to the top where the pebbles are, the gravel is. [It’s] a long ass haul in that way of getting there. And one of our failings as humans is we’re always looking for more comfortable ways of getting things that make life easier. Life was meant to be a challenge … And this, all these efforts to try to overcome what we don’t know by getting to know them. The wonderful imagination, pursuit of imagination, itself is really key to all of this … what’s going on right now is just the lack of imagination. I think we all agree to that. And you can’t really be a good fisherman without having an imagination … I don’t care if I catch the fish anymore, I just want to get [a feeling].

MO: Did the dam removal at the Elwha River give you hope that we can do this on a bigger scale with the Snake River and in other rivers?

TS: As long as we have a healthy river, we have hope. If we don’t have a healthy river, we don’t have hope. Open and shut. And now [the Elwha is] a real river that it once was. And it’s a hydrant to climb up and we’re going to get some of those big long fish that used to be 3 feet long. The Natives told me about their grandmother walking from the tail and taking three steps to the head of the fish. I don’t think they come any bigger. But it’s from the workout. It’s from the trial and error.

MO: You’re at this point in your career where you’ve got this pulpit. What is the honest message people need to hear from you about conservation?

TS: I think my concern really is that we’re doing everything now for our own good. And not just [with] the river. But what it really means is our life. Where does it start? Where does it go? The train goes by the whistle. Where’d it come from? Where is it going? I always want to know … That’s really what we’re talking about with salmon going upstream. It doesn’t kill them. It just makes them stronger. And that’s really what we have to know that we can only become stronger individually by how much we’ve tried to overcome difficulty. Because at one point, you have to have difficulty. You cannot have the computer make your life easier.

MO: How do we change?

TS: Einstein said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge” because it feeds it. Dammit. Feed it good things. Give them the river to fish. Give them the river to enjoy. Give them the river to feel as I did as a 5-year-old kid putting my legs in the river, feeling the water rush by. Put our feet in the river. Let’s react to it in a way that makes us feel …

That’s what A River Runs Through It is about. All this other stuff that I’m talking about is how the river gets together. Our lives at the end—and I’m finding at my age—it all just becomes one … it’s all about what we feel, and we’ve got to begin to feel again … We’ll never really know how to verbalize that. Because in the end, most of this stuff is really about what we feel … I understand that “eventually all things merge into one and the river runs through it.”

Bella Butler and Cameron Scott contributed writing and reporting to this article.

Brian Ladd is a father and real estate agent in Bend, Oregon. At Ladd’s wedding more than 20 years ago, his brother, Eric, showed a clip of A River Runs Through It, and the circle was completed when Ladd had the opportunity to sit down with Tom Skerritt for this issue’s feature article.