Grizzly 399 reigned from her throne in one of the wildest habitats in the Lower 48 for nearly 30 years, mothering 18 cubs and inspiring people across the globe to connect with and protect threatened wild species and places.

BY BRIGID MANDER

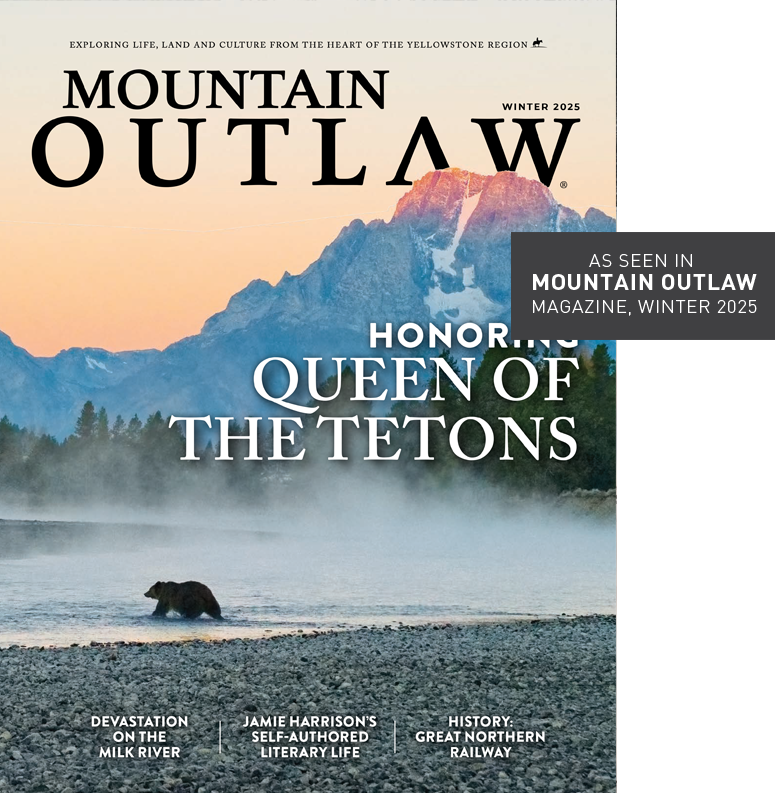

On October 23, 2024, wildlife photographer and Wilson, Wyoming resident Savannah Rose received a text from a friend reporting that a grizzly bear had been killed by a car the previous night on a highway south of Jackson. Rose felt her breath catch in her throat, hoping it wasn’t grizzly 399, a favorite subject of hers and her quarter-million social media followers—and the world, for that matter. But a phone call to her friend, a national park biologist, confirmed the worst: The Queen of the Tetons was dead.

“It was gut-wrenching,” Rose told Mountain Outlaw just days after the accident. “I know she didn’t know me, but she was so dear to me. It hit me like a friend’s sudden death.”

As the news spread from the Jackson Hole valley throughout the world, many who knew of 399 shared Rose’s despondence. A collective acute grief eventually made way for the emptiness that comes from an untimely death, especially one with the ignominy of a vehicle-wildlife collision.

For the reality is, this wild 28-year-old grizzly bear, a member of a native species which white settlers had nearly succeeded in extinguishing barely over a century ago, was a beloved part of life in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Her many superlatives—a barometer for her species recovery, an economic driver, a mother, a celebrity and a catalyst for coexistence—made her inarguably the most famous bear in the world, but also an ambassador to humans, for her offspring and her fellow grizzlies as well as all interconnected wildlife of the iconic GYE. Many of her admirers now hope the call to respectful coexistence inspired by her death can be as resounding as that of her life.

A CELEBRITY, A MOTHER AND AN ECONOMIC DRIVER

When 399 was born in the winter of 1996, grizzly bears had been federally protected as threatened by the Endangered Species Act for just over two decades. She was tagged and collared in 2001 as female grizzly No. 399 for tracking and identification by researchers. For the next couple years, she lived a quiet life, monitored and known mainly by biologists, and was the first bear known to have taken up residence in Grand Teton National Park since attempts to exterminate the bears more than a century ago.

That changed in 2006 when globally renowned, Wyoming-based wildlife photographer Thomas Mangelsen noticed 399 near Oxbow Bend in Grand Teton. Mangelsen noted the mama bear was consistently spending time in areas visible from the road, even savvy enough to look both ways for cars before crossing the roads with her cubs. Ostensibly, 399 had deduced she and her young offspring were safer from male grizzlies—known to kill cubs not their own so they can mate with the female—if she stayed near roads and humans. Mangelsen was intrigued, and throughout the following years, he and conservation writer Todd Wilkinson documented and shared her image and stories.

For wildlife tourism, a 399-and-cubs sighting became a magical objective. Professional and amateur photographers snapped cumulative millions of images. Although her first known cub had died during its first summer, her next set of three cubs, born in 2006, stepped into the limelight with her. In 2007, 399 attacked a hiker who surprised her and her then- yearling cubs on a carcass, knocking him down and biting him. The hiker, who survived with minor injuries, pleaded for mercy for the bear as wildlife officials considered “removing” her from the population (agency speak for killing the bear).

Dr. Chris Servheen, who was at the time in the middle of his 35 years as the grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was the decision-maker on whose word 399’s fate hinged. He declared the bear had acted naturally, and 399 was left alone. Servheen may have had no idea then of the implications of that decision, but it proved to be an important inflection point in which the human right to recreate in bear territory no longer always trumped the bear’s right to live. Two of those cubs, however, were eventually killed by humans anyway: one by a hunter outside the park and one for predating on unattended livestock within the GYE. The surviving female of that litter, grizzly 610, is now nearing 19 years of age. She went on to have her own cubs, and like her mother, has spent time visible to humans, garnering her own following of wildlife watchers, despite being known for a less serene and tolerant demeanor toward the masses than 399.

From then on, throngs of admirers hung on every move 399 made. Her chosen proximity to humans opened a window through which people could watch individual bears living their own wild lives. People witnessed 399 teach her cubs to cross rivers, to hunt and navigate around the humans who gathered for her roadside spectacles. Word spread far and wide of the legendary bear that tolerated hordes of humans looking at her. People traveled from around the world to see her. Her fans and paparazzi caused “bear jams” of hundreds of cars. Wildlife managers gave up on the idea of hazing the bear from the road and instead hired more staffers to manage the people so 399 could get her grizzly bear business done.

And her business was hot news: 399 is out of her den! 399 has one cub this year! 399’s small cub was killed by a hit-and-run driver; she has removed the little body from the road, laid it under a tree, and has been wailing by the roadside all day. 399 was seen on Teton Pass! 399 is safe in her den for the winter. 399 is too old for any cubs, but wait, now she has four cubs! An adult son of 399 was killed for human-caused conflicts. 399’s daughter, 610, has adopted one of her younger siblings from 399. 399 and her cubs got into unsecured beehives. Five grizzlies walked through downtown Jackson last night (399 and her four giant cubs) with a police escort to ensure the bears’ uneventful passage and safety through town. There was a book. Then another book. A PBS special. People couldn’t get enough of 399. Then, in 2023, 399 became the oldest female grizzly in the GYE to have a cub, utterly delighting her legion fans. This further cemented her identity as a mother, having 18 known cubs over the span of her 28-year life, and at one point raising four cubs at once, which is rare.

Such intimate observation also shifted a standard research stance to avoid humanizing wildlife.

“Anthropomophization is supposedly a no-no, as if animals cannot have feelings or thoughts of their own,” Mangelsen told interviewers from PBS Nature after 399’s death. “Jane Goodall began the path to debunk the idea animals don’t have their own feelings, and the story of 399 is a really sentient story.”

For the younger generation of wildlife advocates like photographer Rose, born the same year as 399, the idea animals have no feelings is a total fallacy. “399 addressed people’s separation from wild spaces, and awareness of wildlife,” Rose said. “People want to connect with animals, and she bridged this in a way that taught thousands of people that grizzlies are sentient, intelligent beings. She was still a grizzly. I saw her hunt and kill elk calves, and discipline her cubs brutally, but she was a very special animal. It’s wonderful to love someone just for what they give the world, and people’s relationships with her were beautiful.”

It was the unique combination of wildness and a pointed tolerance for humanity which made 399 such an impactful ambassador for wildlife and wild places.

“I fell in love with her because she is a very personable bear,” said Trevor Bloom, a botanist with the Bridger-Teton National Forest which borders Grand Teton National Park, and a longtime wildlife guide. “She made it easy to watch, and it’s nice to see animals where you know their stories. It makes it easier for us to relate to them; it’s hard to understand and care about wildlife if you have no experiences with them.”

While there’s no exact figure quantifying the economic impact of 399’s allure, tourism is the second largest industry in Wyoming and growing, closing in on $8 billion a year. In 2022, almost 2 million overnight visitors came to Teton County, pumping $1.65 billion into the local economy. A recent National Park Service study also reported economic impacts specific parks had on gateway communities in 2023, with Grand Teton visitors spending an estimated $738 million in local gateway regions, supporting a total of 9,370 jobs and generating $936 million in economic output. The study found visitors to Yellowstone spent $623 million in gateway regions, supporting a total of 8,560 jobs and producing $828 million in economic output. It’s hard to disentangle these figures from one of the parks’ top allures—wildlife—and even more specifically in many instances, 399.

It’s a wonder that in a world where European settlers so ruthlessly worked to tame the environment for human consumption, booming visitation to watch a mother grizzly reveals a craving to be near wildness, and to gain a connection to something bigger.

A BAROMETER FOR RECOVERY

Historically, grizzly bears inhabited the western half of North America from central Mexico to Alaska and played a key role in healthy ecosystems. Native Americans have lived with grizzlies as neighbors for thousands of years, familiar with both their peaceful side and their ferociously protective side. Tribes had varying views and legends around grizzlies, but common threads were an association with courage and strength, protection and healing, resilience and wisdom. Some legends suggest people who possess bear medicine have the courage to stand up and fight for what is right.

Biologists at the USFWS estimate prior to 1800, upwards of 50,000 grizzlies lived in the Western U.S. between the modern borders of Mexico and Canada. Like wolves, bison and Native American tribes themselves, the presence of grizzlies on the landscape was a perceived obstacle to homesteaders and their domestic livestock as they pushed west looking for land and resources. A purposeful campaign to eradicate grizzly bears was launched in the 1800s, partly funded by a government-bounty program, which resulted in the widespread shooting, poisoning and trapping of the bears.

By the 1930s, grizzlies occupied just 2 percent of their traditional range and only approximately 2 percent of their former population remained. By the time early conservationists in the 20th century mobilized to prevent complete extirpation, there were fewer than 800 grizzlies in the Lower 48. These remaining individuals were confined to disconnected, small areas of wilderness and conserved lands like Yellowstone National Park, where the last remaining individuals of other species that had been hunted to near extinction in the same 100 years were also found, such as trumpeter swans and bison. The GYE had just 136 living grizzlies in the 1970s.

Researchers, particularly John and Frank Craighead, who became famous for studying the Yellowstone grizzlies in the 1960s, advocated for the bears’ intelligence and their critical role in the ecosystem. The Craigheads coined the term Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which today refers to an approximately 22-million-acre area surrounding the 2.2 million acres of Yellowstone National Park. Grizzlies received federal protection under the newly ratified Endangered Species Act in 1975 but remain incredibly vulnerable to human activity.

As grizzlies recovered, 399 was the first grizzly known to reside in Grand Teton National Park where she would emerge from her den each year near Pilgrim Creek. Her lifespan marked much of the period of a slow grizzly recovery.

“[399] is representative of the reoccupation of the whole Jackson valley by grizzly bears, and even south of there—that all happened during her lifetime, and all her offspring are contributing to that,” Servheen, now retired from the USFWS, told PBS Nature. “She taught us grizzly bears are not this demon species that some people like to think of them as—that they are always out to get you or kill something. She could navigate an amazingly complex environment of people in the park, and residences outside the park. She was a symbol of wild nature reoccupying some of the most beautiful country left in the United States.”

According to the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, a multiagency government group founded in 1983 that oversees the established geographic areas of grizzly bear recovery, under protection of the ESA grizzly populations in the U.S. climbed slowly from less than 800 to about 2,200 today. States such as Wyoming, Idaho and Montana are now advocating to replace federal delisting with state management, which would open the bears to trophy hunting seasons. But this has been a massive conflict in recent years, where both sides have battled it out in courtrooms—and sometimes in the comments of social media posts about 399.

At the time of 399’s death, at least 68 other grizzlies in the GYE population had been killed in 2024, all but one due to human causes, according to IGBC data. Delisting opponents cite these deaths, slow population growth and the fact connectivity between populations has not been reached, as bears in the GYE remain isolated from other populations.

Human conflicts such as livestock depredation remains a challenge with grizzlies on the landscape. Some ranchers claim there are too many bears, while wildlife advocates say there’s too much livestock grazing on public lands in otherwise functioning ecosystems. For Servheen, who is now the president and board chair of the Montana Wildlife Federation, delisting grizzlies is no longer the right path forward. Previously, biologists and scientists made wildlife management decisions at state agencies to work toward healthy wildlife populations. But when states allowed for extensive, politically driven legislation and policies that opened hunting opportunities for wolves after their delisting, it sparked dire concern among wildlife biologists on the fate of grizzlies.

“Increased political interference from state legislatures over biologists, and recent, regressive policies in the states put grizzlies at the greatest risk,” Servheen said, citing Idaho and Montana’s 1800s-style management, including bounty killings meant to dramatically reduce wolf populations as an example. “When politics supersede science, things go badly for the wildlife.”

The recent, rapid rate of development of private lands in wildlife habitat in the GYE is also a tremendous threat to all wildlife, including grizzlies, according to Servheen. “The cumulative effect of all this development is compromising huge areas of grizzly bear habitat. All these areas are now being filled with people, and they also want to recreate in adjacent public lands, endangering the wildlife,” he said.

Such development is also what gives way to increased traffic, which has detrimental impacts on sensitive ecosystems, as evidenced by 399’s death. Migratory and wintering ungulate populations also suffer tremendously, usually with little public attention. Even in Jackson, along a stretch of Broadway where speed limits are lowered to 30 mph to protect wintering mule deer crossing the five-lane road to connect habitats, drivers speed. The bodies of vehicle-killed mule deer that tried to cross can be seen crumpled on the sidewalk in winter. In the state of Wyoming alone, more than 7,500 big game animals are reported killed on Wyoming roads each year, an average of 21 individuals a day.

“What happened to 399 reflects the problems of our community; it was a symptom of the sickness of overdevelopment,” Rose said.

In recent years, the state of Wyoming has poured resources into identifying and building wildlife over- and underpasses around the state, and in Teton County, recent crossings have been built where mule deer, elk and moose often cross. Twelve more slated for construction in Teton County will be built in order of critical priority. (The spot where the elk which led to 399’s death was killed is the third lowest priority crossing on the list). Taylor Phillips, a wildlife guide and owner of Eco-Tour Adventures, founded WYldlife for Tomorrow, a nonprofit through which businesses donate to Wyoming Game and Fish’s funding for projects like wildlife crossings and habitat restoration. “We have an incredible responsibility to protect our ecosystem, and show people what we value,” Phillips said.

Amid solutions, increasing development remains an issue. According to Luther Propst, a Teton County commissioner and former conservation attorney, the huge profits developers can reap in Teton County and intense pressure for growth in a desirable place to live, visit or own a trophy home is an insidious problem. Spaces for small businesses and the homes of contributing local residents are continually lost to multi- million-dollar luxury homes and short-term rentals, and while the total population of Teton County isn’t growing, the vast number of service jobs is exploding, creating an unhealthy socioeconomic situation for humans. For wildlife, it is critically dangerous, as soaring worker traffic combines with vehicular deaths, loss of habitat and connectivity.

“It’s harder for wildlife advocates to fight this kind of threat versus threats of yesteryear, like logging and mining,” Propst said. “More hotels, tourism and high-end and trophy home building have real impacts. They require a lot of workers to keep these things going, which creates a mainly low-wage workforce serving these industries, who often are commuting in and out through wildlife corridors.” Indeed, the Subaru that fatally struck 399 was driven by a late-night commuter leaving Jackson after working his job to return home in an outlying community.

When news of the famous bear’s death shot around the world, tens of thousands of fans mourned, many posting tributes on social media. The story was picked up by The New York Times, ABC, CNN, USA Today, The Washington Post, the AP newswire and many other national outlets. Foreign media covered the story. Federal and state wildlife managers and land managers felt compelled to make public statements, including Chip Jenkins, superintendent of Grand Teton National Park, where the bear spent most of her life.

“The grizzly bear is an iconic species that helps make the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem so extraordinary,” Jenkins said in a news release. “Grizzly bear 399 has been perhaps the most prominent ambassador for the species. She has inspired countless visitors into conservation stewardship around the world and will be missed.”

A CATALYST FOR COEXISTENCE

Although the vehicle that struck and killed 399 was deemed not at fault, the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office kept the driver’s identity tightly sewn up due to a flood of angry communications and hateful online comments. Thousands worried over the fate of Spirit, the year-and-a-half-old cub with 399 when she was killed. Biologists assured the public the cub’s chances of survival were very good. A makeshift memorial in Jackson’s Town Square enshrined 399, made up of piles of notes, mementos, tributes and calls to act against potential delisting of grizzlies from the ESA. People asked the governor of Wyoming’s office to declare flags be flown at half-mast. The office declined—respectfully.

People were grieving, but they were also angry. They were angry that authorities reportedly knew grizzlies were around the highway and took no action to warn drivers; angry that grizzlies were feeding on the carcass of a road-killed elk that should have been removed by authorities; angry that in just the last decade, a once-quiet scenic byway frequently crossed by wildlife has exploded with constant construction- and service- industry traffic, a downstream effect of Jackson’s ballooning development. And yet, if channeled into efforts to better coexist with grizzlies, this anger, combined with action, could bring a silver lining.

In 2011, wildlife biologist Jenny Fitzgerald was hired as a bear ranger in the park, part of the growing battalion of National Park Service employees on the 399 team. “That was the year 399 and 610 were out with five cubs total. It was my job to know where they were, manage crowds, stop traffic, and move humans,” said Fitzgerald, who later worked for the park service in California studying mountain lions, including P-22, another famous wild animal.

In 2012, P-22 was discovered living in Griffith Park near the white Hollywood Sign in Los Angeles. He had miraculously survived crossing both Interstate 405 and U.S. Route 101, two of the busiest highways in the world, but was then isolated in a small habitat and cut off from potential mates by the traffic. P-22’s life in the park and unsuccessful search for a mate enthralled people around the world. In 2022, at roughly 12 years old, he was euthanized after sustaining severe injuries from a vehicle strike, but documentation of the big cat’s life had already educated millions of people about wildlife and the impact of human development on them.

P-22’s legacy galvanized support for the world’s largest wildlife overpass, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing. Currently under construction over the 10 lanes of the 101, it will connect the Santa Monica Mountains to the Simi Hills. It’s too late for P-22, but the crossing will allow mountain lions and other animals safer habitat connectivity. Scheduled for completion in 2026, the nearly $100-million project received $44 million in private donations from people inspired by P-22’s story.

Fitzgerald is now executive director of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, a nonprofit which advocates for wild animals and protection of wild landscapes. “399 was this experiential catalyst—she made people care about grizzly bears as incredible, wild, sentient beings,” Fitzgerald said. “How can we capitalize on her legacy, to honor what she did for her species, and humanity’s connection to wild animals, and to coexist with wildlife? After all, if Jackson is so passionate about our wildlife, we need to be a flagship example for other places.”

In Teton County, during and after 399’s forays south of the park through residential areas in Wilson and Jackson, lax rules around wildlife attractants changed quickly. Constant human failure to secure trash properly forced Teton County to mandate new, self-locking cans in 2022. Chicken coops and apiaries had to be secured with barriers like electric fencing, and a recent push to allow bees and chickens in town limits was denied. New fruit-bearing trees are prohibited, and existing ones must be harvested completely of fruit. To give the regulations actual teeth, Teton County recently hired two compliance officers to investigate residences and issue warnings, with a final step of $750 per day penalties for noncompliance.

“Discussions at the town and county had been going on for years about this—but 399 walking through downtown was a big catalyst,” said Tanya Anderson, who holds the newly created position of ecosystem stewardship administrator for the Town of Jackson. Area groups have stepped up to support these efforts, like Wyoming Wildlife Advocates, which sells self-locking cans at cost to residents.

“Coexistence in the GYE is the most important part of 399’s legacy,” said Wyoming Wildlife Advocates Executive Director Kristin Combs. “Having regulations is a big part of protecting bears and wildlife. People need to be faced with adverse consequences. [Since the county announced such consequences], my phone has been ringing off the hook with people trying to get

into compliance.”

Most onlookers hope the outpouring of emotion over 399 will continue to have a positive impact for wildlife.

“We don’t want to forget about the wildlife when the pressures of the world are just to always make more room for humans,” said Bridger-Teton National Forest’s Bloom. “I hope 399’s legacy will be to educate more people on coexistence, on the Endangered Species Act, and bring attention to the magnitude of the problem of wildlife getting killed by cars every day.”

After the furor and sadness from her death, 399’s vast following became stuck on one logistic: what would happen to her body? A few floated the idea of taxidermy, but the majority of people reacted to this option like stuffing a beloved relative. Thousands of her fans pleaded publicly for her body to be returned to the earth. The USFWS remained mum on the subject until a Nov. 1, 2024 news release. In it, the agency announced it had honored the legacy of 399 by cremating her body. Officials then returned her ashes to Grand Teton, where they were spread at Pilgrim Creek.

Grand Teton’s Jenkins released another statement: “399 will always be part of this special place,” he said. “However, there is still work to do to ensure her descendants and all grizzly bears continue to thrive in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. It’s up to all of us to make sure they do.”

These are unprecedented events in wildlife management: a grizzly cremation, the somber spreading of ashes, and condolences offered by officials. But then again, nearly everything about 399 was unprecedented. She paved a path for wildlife and reminded humans how rich a shared world is—and could be. As grizzlies expand beyond protected federal lands, county governments and communities in and around the GYE must decide what they value, and how they are willing to act and adjust human behavior to protect those values. This would be the most unprecedented honor to 399’s legacy of all.

Brigid Mander is an adventure and conservation journalist based in Wilson, Wyoming.