Running the Grand Canyon, Rim to Rim to Rim

WORDS AND PHOTOS BY MIRA BRODY

Te color of the trail beneath our fast-moving feet changes according to where we are on this mile-deep map of geologic time that dates as far back as 1.84 billion years. A cross-section of this kind of history can only exist here, in the Grand Canyon. With each step, we gain distance but lose time—the push and pull of submitting yourself to a vast landscape. Currently, we’re somewhere in Redwall Limestone, a 500-foot band formed during the Mississippian age more than 300 million years ago. Blood-red dusty proof stains my shoes. A canyon hiker steps aside as our crew of three women run by, the first rays of the morning sun warming our skin on an otherwise chilly November morning.

“Are you doing all three rims?” the hiker asks us, the first of many times we’d be asked that question on our long journey. “Today?” he asks. Time is relative down here. Distance however, is not.

We tell him yes between short breaths and the hiker exudes a sound somewhere between admiration and disgust. I feel the same.

Grand Canyon National Park sees more than 6 million annual visitors. Ninety-nine percent of them view it from the visitor center, taking in the great chasm from above; and some hike portions of it from nearby trailheads. A lucky few snag coveted backcountry campgrounds along the canyon’s base and backpack at a leisurely pace.

Fewer still choose to run its entire breadth twice in a single day—my friends and I among these indulgers of Type 2 fun.

With three rims to summit and descend, Rim to Rim to Rim, or R3 as it is succinctly referred to, is a not-so-succinct undertaking. From our chosen route—starting at South Kaibab trailhead, summiting at North Kaibab trailhead and concluding at Bright Angel trailhead—we cover 48 miles and over 11,000 feet in elevation gain.

The experience is as much individual as it is communal. R3 is a globally revered bucket list accomplishment for thru hikers and runners and while we’ll spend many miles of the day alone, there’s a small migratory community inside the labyrinth of the canyon all striving for the same goal in the same giant hole in the ground. We see each other only for brief moments in time, exchange a nod, greeting or intel about the last few hours of our lives. And then, never again.

We cross paths with a woman in her 50s just shy of the North Rim who has run the Grand Canyon every single year for 15 years. This year she invited a friend, a first-timer, to the sufferfest and asked us to pass along words of encouragement to her a few switchbacks down. Then, while refilling water at the Manzanita water spigot, we meet a man from Oregon and gleefully compare bagged goo flavors, a delicacy on the trail.

The day wanes and we exit the snow patches on the canyon’s chillier north side, accidentally startling an older gentleman as he slowly and steadily works his way back to Phantom Ranch where he’ll stay the night. We had seen him hours previous when he was climbing the North Rim, boasting that he had just turned 70.

Deep in the lower gorge, the ground is a light yellow-brown as our feet pound the Vishnu Schist layer, more than 600 million years old. Bright Angel Creek, which we’ve followed for most of the afternoon, fills the otherwise quiet trail before flowing back into the Colorado River. Lights from a passing campground flicker on as darkness descends. Campers are preparing dinner and I almost wish I could stay down here with them, in this alternate layer of time. Instead, we’re pulling clothes out of our packs as the otherwise warm fall day fades in time for our third rim, and final climb.

There is no sunset 6,000 feet underground. One minute there’s a faint light glowing from the edge of the rim above us, and the next we’re crossing the Colorado River in complete darkness.

Our company dwindles down to a few headlamps twinkling in the void that swallows us. Without any indication of distance, these bobbing lights appear to be either 10 or 1,000 feet away, indistinguishable from the galaxy that has appeared above our heads. Unless we pause to look up, our world is limited to the 2-foot halo cast by our own headlamps for the entire 9-mile ascent from the river. Even the colors of the rock layers are invisible, our sense of deep time erased.

Suddenly, a change in pressure and a 25-degree drop in temperature hits us with a chilly headwind. We are out of the inner gorge, referred to as “the box,” and walking along the Tonto Platform, a 500-million-year-old layer of impermeable shale that divides the upper canyon from the lower.

We pass another trickling creek and greet two young women we had seen earlier that morning. They are dressed in vibrant Native ribbon skirts that glisten and sway by the light of our headlamps. We plunge back into the darkness for what will be the longest 2-mile so-called run of my life, following a series of meticulous switchbacks that hug the side of the upper canyon wall.

The Kaibab Limestone layer was formed 270 million years ago, which is approximately how old we feel as we crest the final rim of the stuff and hobble through the parking lot. Forty-eight miles on the body and soul is an intimate feeling, a mixture of pride and pain. Part of you wants to curl up and never walk again; but there’s another, smaller part of you that wonders how much more you might be capable of.

It’s 10 p.m., exactly 15 hours and 17 minutes from our start. The parking lot is as sparsely filled as when we left it, the sky just as dark. The three of us girls get into our car and eagerly pass around a Ziploc bag of cold pizza as we unceremoniously ponder what we’ve done.

We share a collective sigh: a mixture of relief, exhaustion and accomplishment and somehow embodies that entire span of time—a span that included millions of years of geology, a community of people and an entire landscape.

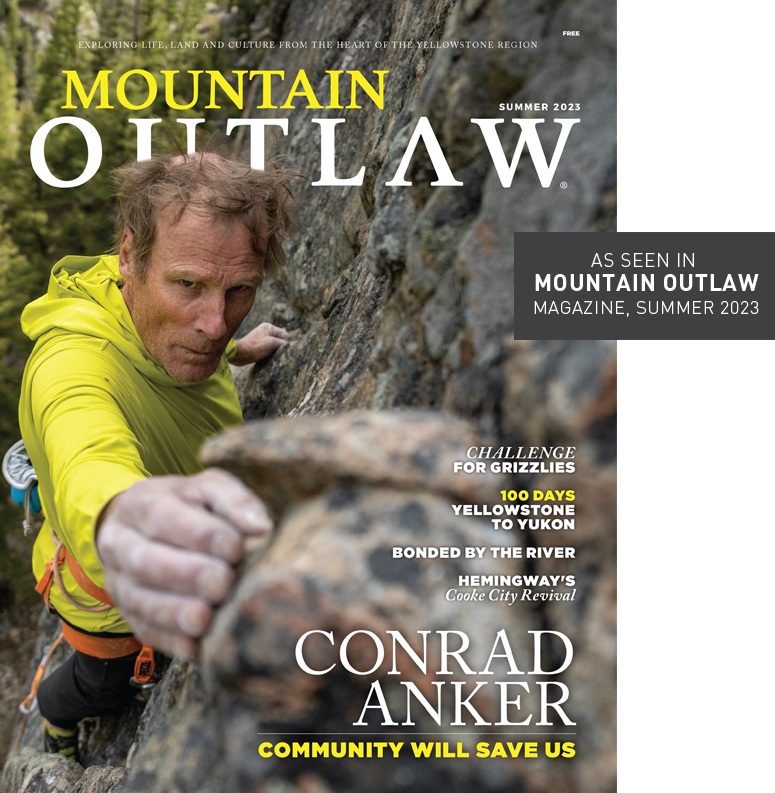

Mira Brody is an avid runner and writer in Bozeman, Montana. She is the producer of Mountain Outlaw and content production director at Outlaw Partners.